My current

work focuses on the role of partners of venture capital firms who make angel

investments on the side. What that allows us to do is compare organizational

decision-making to individual decision-making. In this work, we find that

individuals acting alone are able to process private information that they have

that their organization doesn’t have, and allows them to make investments in

firms with observably weaker characteristics, such as younger founding teams,

less educated founding teams. Nevertheless, these individual investors are able

to generate the same financial return as their employing firms.

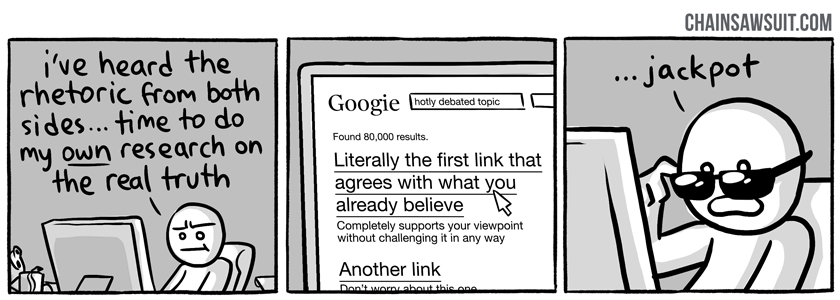

What does Wu mean by private information? Well, he's really referring to tacit knowledge... expertise that cannot be easily transmitted to others. Your intuition may tell you that a certain investment is attractive or not. The data do not justify your conclusions. How do you persuade your partners in the firm? Wu argues that you often do not persuade them. You can't make a strong, rational, explicit case to them. However, tacit knowledge leads you to conclude that it's a good investment. Groups, Wu argues, focus on explicit information and often fail to incorporate crucial tacit knowledge.